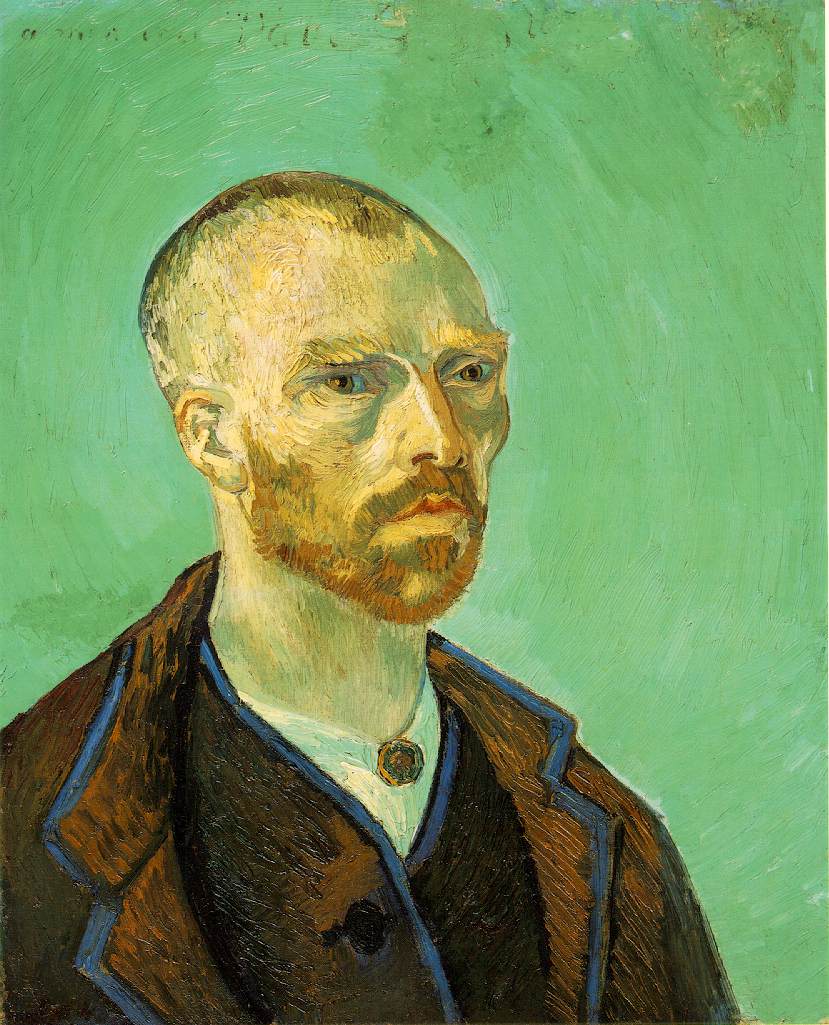

Vincent van Gogh made an incredible splash on the art scene before he committed suicide at the age of 47, after spending 70 days with his esteemed friend, Paul Gachet. Van Gogh was a fantastic artist and is accredited with many works of art, yet a debate arises when certain pieces cannot be directly attributed to van Gogh himself and their provenance seems to be lost in the tussle of some museums’ desire to acquire his artwork. The family of Gachet is well-known to have sold pieces of artwork that were of questionable origin, since he himself and his son were aspiring artists who had a knack for imitating pieces. The debate about the origin of these paintings, though heated, has two sides. Both Per Hedström and Britta Nilsson, who wrote one article, and Michael Kimmelmann, who wrote another article, analyze what is to be done with van Gogh forgeries and if fakes have any artistic merit.

In the article by Hedström and Nilsson (Per Hedström and Britta Nilsson, “Genuine and False van Goghs in the Nationalmuseum” from Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum Stockholm 7 98-101 2000), one painting in particular is questioned. “The Cornshocks,” of which there are two similar copies and therefore the question arose, is believed to have been forged as a van Gogh. Its copy in the Nationalmuseum is said to have been painting on a cardboard canvas using some cadmium yellow coloring. The article states that no other painting by van Gogh displayed these characteristics; therefore it had to have been a fake. Yet another clue points to forgery in that the other copy, that was in the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio, was produced in Auvers in 1890. Auvers is the exact location of the Gachet residence and where the family could have reproduced the painting and claimed it as a van Gogh after his death. This article incorporated stylistic elements of the works to try to prove that one was a forgery. Some people have decided that the Nationalmuseum’s version is a sketch for the Toledo one. Both paintings were analyzed and the Nationalmuseum version was decidedly a forgery. The basic idea is that technology can disprove a painting to be a fake and therefore forgeries should not be on display.

In the New York Times article by Kimmelmann, the changing societal feelings about forgery are examined. With regards to van Gogh and the Gachets, forgery had, but that time, become almost criminal. Apparently the Gachets knew this, and acted very strange about the paintings they claimed were by van Gogh. They refused to lend them to exhibitions and were very reticent to let people see them. But instead of taking this odd behavior as a single that some paintings could be fraudulent, the article supposes that the paintings could have just been done van Gogh’s bad days, and therefore are sub par when compared to his other works. Kimmelmann also states that when the Gachets copied or imitated other works of art, they signed it with their own name or clearly labeled them with their pseudonyms, so as not to have any confusion with the real artists themselves. The article also provokes the idea that scandal about the artwork brings in more visitors, and thus more people are exposed to works of art, be it fake or not. The author implores us to consider looking at the painting for what it is, yet regrets that the authenticity is really what gives it value. The quality is not as important as if the artwork is really by van Gogh, or some other renowned artist. The argument is that we, as humans, need authenticity to stay in reality and have a hold on what is our real history.

Both articles analyze the artwork, or supposed artwork, of Vincent van Gogh in different lights. When forgery becomes an issue, it not only affects the viewer’s opinion about the artwork, but it also affects the psychology of the viewer. We value authenticity, especially with van Gogh paintings, not only for its monetary quality but also because it is the foundation of our history and marks when real events happen. If everything was a forgery, there would be no history.

1 comment:

van gogh was 37 not 47 when he died

Post a Comment